Double-crested Cormorant Nannopterum auritum Scientific name definitions

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Американски корморан |

| Catalan | corb marí orellut |

| Croatian | žutogrli vranac |

| Czech | kormorán ušatý |

| Danish | Øreskarv |

| Dutch | Geoorde Aalscholver |

| English | Double-crested Cormorant |

| English (United States) | Double-crested Cormorant |

| Finnish | amerikanmerimetso |

| French | Cormoran à aigrettes |

| French (France) | Cormoran à aigrettes |

| Galician | Corvo mariño de orellas |

| German | Ohrenscharbe |

| Greek | Αμερικάνικος Κορμοράνος |

| Haitian Creole (Haiti) | Kòmoran lanmè |

| Hebrew | קורמורן אמריקני |

| Hungarian | Füles kárókatona |

| Icelandic | Skerjaskarfur |

| Japanese | ミミヒメウ |

| Lithuanian | Ausuotasis kormoranas |

| Norwegian | totoppskarv |

| Polish | kormoran rogaty |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Corvo-marinho-d'orelhas |

| Romanian | Cormoran urechiat |

| Russian | Ушастый баклан |

| Serbian | Žutogrli vranac |

| Slovak | kormorán ušatý |

| Slovenian | Zlatogrli kormoran |

| Spanish | Cormorán Orejudo |

| Spanish (Cuba) | Corúa de mar |

| Spanish (Dominican Republic) | Corúa |

| Spanish (Honduras) | Cormorán Crestado |

| Spanish (Mexico) | Cormorán Orejón |

| Spanish (Puerto Rico) | Cormorán Crestado |

| Spanish (Spain) | Cormorán orejudo |

| Swedish | öronskarv |

| Turkish | Kulaklı Karabatak |

| Ukrainian | Баклан вухатий |

Nannopterum auritum (Lesson, 1831)

Definitions

- NANNOPTERUM

- auritum / auritus

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Introduction

Double-crested Cormorants are common inhabitants of seacoasts and inland waters, rarely observed out of sight of land. They may be seen swimming low in the water, often with little more than their heads and sinuous necks showing, but they are more evident at daytime resting places on rocks, pilings, or trees. Resting birds often hold their wings spread, a characteristic posture of many cormorants thought to aid in drying wet feathers.

Cormorants dive from the surface and hunt their prey underwater using powerful strokes of their totipalmate feet (in which all 4 toes are connected by web, as in other pelican-like birds). The prey may be schooling fish or bottom-dwelling fish and invertebrates; a great variety of species have been reported. Cormorants are gregarious birds, often nesting in large numbers at diverse sites—on the ground on islands free from predators, in trees, or on various artificial structures. These colonies are conspicuous, not only because of the visible whitewash but also, downwind, because of the powerful reek of guano and rotting fish.

The Double-crested Cormorant is the most numerous and most widely distributed species of the 6 North American cormorants. In the U.S. and Canada, it is the only cormorant to occur in large numbers in the interior as well as on the coasts, and it is more frequently cited than the others as conflicting with human interests in fisheries.

Cormorants have been viewed negatively throughout history and recent increases in numbers have spurred renewed controversy; driving new regulatory changes, management, and research. These increases have been most notable in the north and east of the breeding range (subspecies P. a. auritus) and where these birds winter in the southern states, especially near catfish farms.

Cormorants feed opportunistically on fishes that are readily available and often congregate where these fishes are easily caught. In natural environments, fish species of direct interest to recreational or commercial fishermen typically do not make up a large part of the cormorants' diet (see Diet section and Appendix 1). Exceptions do occur, however, and cormorant impacts to commercial and recreational fisheries, including economic impacts, have been documented. Cormorant impacts to island vegetation and co-nesting species have also been documented. However, the biological and economic impacts attributed to cormorants, especially fishery impacts, are often complex and difficult to establish unambiguously.

The increasing abundance of cormorants and real and perceived resource conflicts have resulted in substantial federal policy changes regarding cormorant management in the US (USFWS 2009, Dorr et al. 2012c, Weseloh et al. 2012). The most significant regulatory changes were the establishment of the aquaculture depredation order (AQDO) in 1998 and the public resource depredation order (PRDO) in 2003 (USFWS 2009). These rule changes allowed for significantly greater cormorant management, including egg-oiling and culling by state, federal, and tribal entities in the US. Cormorant management efforts have also been conducted on their breeding grounds in Canada, but management and policy vary widely on a province-by-province basis.

Increasing cormorant numbers, management efforts, and policy changes have led to considerable research investigating cormorant biology, impacts to resources, and effective management of the species. Several symposia have been focused on these subjects including volumes, edited by Nettleship and Duffy (1) and Tobin (2), which addressed conflicts and other aspects of the species' biology and history. More recently, Stapanian (2002) published a volume on interspecific interactions, habitat use, and management and Weseloh et al. (2012) published a volume on impacts to natural resources, management assessment, migration and movements, and population demographics.

An early species account, principally by R. Arbib, is found in 3: 325–340; for extensive comparative information see 4: 326–353 and 5. Numerous observations from a blind are included in the large account by Mendall (6); also, see 7. A recent bibliography (8) includes more than 1,300 titles (through 1995). In Europe, the ecological counterpart of this species, the Great Cormorant (P. carbo), especially the subspecies P. c. sinensis, has undergone similar fluctuations in numbers and, like the Double-crested Cormorant, is also perceived to be detrimental to human fisheries and aquaculture (9).

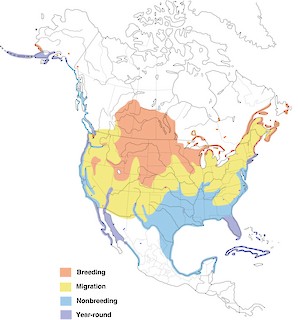

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding

This species also winters in Bermuda in small numbers, and winters locally south to the dashed line. See text for details.